“There have always been romantic and glorified notions about being out at sea that draw people into this idealized 'dream'...I’m curious about the ways in which life at sea embody our fantasy and also counter it.”

We visited Martin at his flat in Russian Hill and though his studio is “officially” in the converted garage space, he pretty much makes work everywhere in his house. Works in progress occupied the front of his living room as well as an office area, and were scattered throughout the expansive, covetable space of his garage. Because Klea and I hadn’t started out the morning with quite enough coffee, we showed up at Martin’s jonesing for a caffeine fix, and luckily for us he immediately offered to make some. There’s something quintessentially

Californian about Martin— he’s laidback, welcoming, easy to talk with, and a bit of a free spirit. In his work too, there’s an element I’ve long associated with “Western” archetypes— that wild-eyed imagination and yearning which strictly belongs to the thrill-seekers, dreamers, individualists, and outsiders who constitute a prevalent part of our cultural landscape and identity. Referencing his own experiences working on ships, notions of adventure, physicality, hard work, and an unwavering awe for the forces of nature are central to Martin’s art. While talking to him, I found myself asking a ton of questions about his time at sea; I wanted to know the particulars of what it’s like to work on a ship, and hoped for long-winded and fantastical stories about his crewmates and the places he had visited. His paintings of churning waves, faraway horizons, and rough-and-ready characters call up a desire most of us have (albeit more latent in some than others): to venture forth and encounter discovery, and to get just close enough to risk to remember what it feels like to be alive.

What mediums do you work with? How would you describe your subject matter? What themes seem to occur/reoccur in your work?

For the most part painting is my medium of choice, but the type depends on the piece and where I happen to be working. If it’s a confined space on a ship or something, then I’ll avoid oils and use water-based paints like gouache on paper. I also like to work on found materials such as nautical charts, old cannery boxes, and driftwood. The sea is the most common theme in my work, but I also like to explore ideas of labor, leisure, escapism, and personal narratives.

Do you have a day job? What is it? What does it mean to you?

I pay the bills with my work on boats/ships. For the most part that is commercial fishing for salmon in Alaska each summer, but I’ve also worked on oil spill response vessels here in the Bay, an international containership, and many other smaller boats. I’d like to possibly try some tugboat work later this year, or maybe a shorter contract on another containership— six months is too long! To me it means freedom, inspiration, and of course a paycheck. I think it’s grounding to work outside the arts as well, you connect with real people and see new places. The art world can be a bit insular, especially in one city.

Can you recall the first time you saw a work of art that had impact on you?

I think early on in my education, Caspar David Friedrich’s work had a big impact on me. He really seemed to find a connection between deep human emotion and nature, which I find interesting— this bond between people and our planet. I think that is part of my draw to the sea; it seems very human at times, partly because we come from it, but also its attributes— like some people, it can be both wild/beautiful and horrible/deadly in the same day.

Is there something you are currently working on, or are excited about starting that you can tell us about?

The show I’m putting together right now for Gallery Hijinks has me excited. I’m working in a lot of different mediums (paint, video, glass, photography), but they are all aiming to expand this narrative about my experience working for six months on a containership.

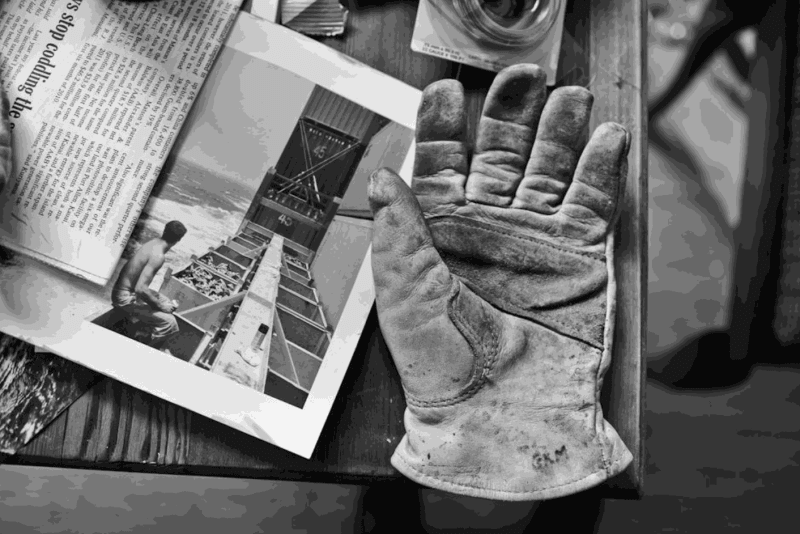

Each piece goes off on its own little tangent, exploring the past and present of shipping and the romance/realities of a life at sea. In a few pieces I borrowed from the style of the Mexican artist Dr. Lakra, which he sort of borrowed from old film posters and his work as a tattooist. I thought the techniques of overlaying imagery worked perfectly for exploring some of the concepts I wanted to touch on; juxtaposing images of my crewmates with more romantic shipping imagery. I’m interested in people’s dreams and influences that shape their lives. I think it applies to us all, really, in any occupation or path, but I focused on why people begin working on ships, which was a question I asked most of my crewmates. All of the imagery has special significance; some are taken from my own photos and others were sourced later from old magazines, the Internet, books, or old Sailor Union of the Pacific newspapers. There are some historical images of key figures in shipping, such as Andrew Furuseth and Harry Lundenberg, both Norwegian sailors who came to America and fought for sailors rights here in San Francisco. There are also references to Sailor Jerry’s tattoo work, which has been so widely popularized, but was originally made for these sorts of characters to stumble into his shop in Honolulu, Hawaii and find a connection with the art.

There have always been romantic and glorified notions about being out at sea that draw people into this idealized “dream” of what it’s like, but the reality is quite different, and yet it does still encompass some alluring aspects— travel, community and solidarity with your shipmates, a sense of freedom, a closeness to nature. I’m curious about the ways in which life at sea embody our fantasy and also counter it.

What are you currently reading, listening to or looking at to fuel and inspire your work?

Last month I was on a random but wonderful expedition called The Clipperton Projectwhere we sailed three boats and about 20 international artists and scientists out to a remote atoll way off Mexico. The trip was inspirational in itself, but one of the artists from Mexico, Carlos Ranc, put together a huge library (in French, English, and Spanish) for the three-week trip, but covered the books and blacked out all references to each title and author. So I don’t know all of what I read, but it was a great collection, The Lord of the Flies by William Golding was in there, and John Steinbeck’s The Pearl, as well as a bunch of other great works.

I get a lot of inspiration from sea stories, such as the chronicles of Bernard Moitessier, Richard Henry Dana, and Joshua Slocum. I like texts about people leaving society for “paradise.” I’m drawn to these kinds of stories because I’ve always wanted to do that— but I recognize that there are consequences. In thinking about people who leave society for “paradise” I’m forced to confront my boyhood dreams and somehow try to honor them in a way that’s feasible and responsible. There is a coming of age theme hidden in there; a real attempt to grapple with a longstanding inspired goal and what pursuing that would actually mean for my life, my work, my relationships, etc. The truth is, I’d love to just buy a sailboat and get out there, and be at sea and see the world and make art.

What does having a physical space to make art in mean for your process, and how do you make your space work for you?

Over the years I’ve gotten used to working on the go, sometimes out of a suitcase, crashing with friends or something. So I’ve learned to do a lot with a little. It can be really hard though, there’s nothing better than a good workspace. I’m lucky to have tons of room where I’m at now; my current space can accommodate different projects and their needs pretty easily.

Do you see your work as relating to any current movement or direction in visual art or culture? Which other artists might your work be in conversation with?

I think there has been a recent movement back towards nature. Which seems pretty silly that that can even be said, since it is the world we live in, but I think there is some truth to that. I also think that with so many first world countries outsourcing their labor, white-collar people are interested in physical jobs in a curious way, even if they are just watching it on TV. I think folks are inspired by people who choose to work outside of the office. I guess it’s timely for me because my work has that angle, and is looking at sea-faring culture and labor, which most people aren’t too familiar with but they seem to be curious about.

How do you navigate the art world?

I frantically try to keep up, going to openings, magazines, and all that. But there is a good amount of acknowledging that I don’t want to make art about art, usually I’d prefer that my crewmates like my work over the art critics.

What risks have you taken in your work, and what has been at stake?

When I was in art school I finally switched to making work about the sea, even though I’d labored in the maritime industry for years and had surfed most of my life. Before that I had focused on all of these negative aspects of my surroundings. Having grown up in Silicon Valley, office parks popping up all around me really affected me. I wanted to focus on something positive in my life, even if it is escapist or nostalgic. It may sound like a cop out, but I see it as a challenge to make work about a subject that has been overused so much and is innately seen as beautiful. But I hope that people see that I am not just making pretty pictures to sell, that the sea has always been a part of my life, both professionally and personally, and I am genuinely interested in all aspects of sea-faring culture.

A commonly held conception is that artists often make their best work during periods of personal turmoil, have you found this to be true?

I read somewhere that when Willie Nelson was asked, “Why are all of your songs sad?” he answered that when you’re happy you...ride the ride, spend the dough, love the person, etc. but when you’re sad you take the time to reflect on it. I am paraphrasing of course, but I think that it’s true. I am sure that I’ve sadistically suffered for my art at times, hoping it will make it more significant; whether it is spending months at sea or rowing around Alcatraz in a hail

storm. But I also really find inspiration from strong people, who move on through rough times with a smile on their face, instead of whining about how bad their life is.

Do you have a motto?

I’m trying to make, “If you don’t stand for something, you’ll fall for anything” my motto, but I’m still trying to figure out exactly what I stand for. I do know that I try to be real and honest in my work. I try to really get to know a subject matter before representing it in my art. I do my best to be conscious of trends, but not necessarily follow them. I also try to create new techniques and methods rather than hashing out a lot of the same thing.

What has been your biggest disappointment and greatest joy thus far in life?

I come from one of those “anything is possible if you put your mind to it” sort of upbringings. So the blessing and the curse is following through on all of the silly dreams that plague my brain.

Are you involved in any upcoming shows or events? Where and when?

My first solo show will be in San Francisco on May 5th, 2012 at Gallery Hijinks.

In June I will have some work in the first show for The Clipperton Project at Glasgow Sculpture Studios in Glasgow, Scotland.